Mapping the Growth of Disability Claims in America

Where jobs vanish, disability insurance is the safety net.

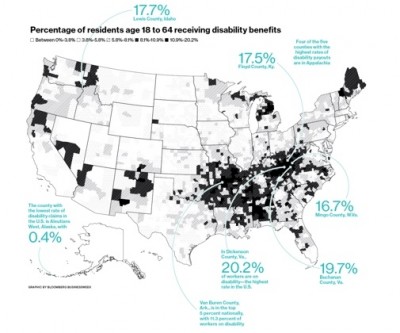

If you’ve paid into Social Security, become injured or sick, and can no longer earn more than $1,130 a month, you can get a monthly subsidy from Social Security’s Disability Insurance Trust Fund. In 1990 fewer than 2.5 percent of working-age Americans were “on the check.” By 2015 the number stood at 5.2 percent. That growth has left the fund in periodic need of rescues by Congress—most recently in 2015, when the Bipartisan Budget Act shifted money from Social Security’s old-age survivors’ fund to extend the solvency of the disability fund to 2023.

“None of us should be surprised that the cost of the program was rising,” says Stephen Goss, Social Security’s chief actuary. He says the program’s growth is mostly a consequence of demographic change. Older workers are more likely to get sick, and as women have entered the workforce, they too have become eligible for benefits.

The geographic distribution of people on disability tells a different, but complementary, story: Workers who might have endured pain for a physical job apply for disability when jobs disappear. This has created what some economists call “disability belts”—rural areas in Appalachia, the Deep South, and along the Arkansas-Missouri border.

In a 2013 paper, David Autor, an economist at MIT, and his co-authors wrote that Social Security disability insurance was the single biggest source of federal transfers into areas that had been directly affected by trade with China and Mexico. Dan Black, now at the University of Chicago, found in a 2004 paper that growth in disability claims in Appalachia dramatically outpaced those in the rest of the country. Although it’s not designed to, Autor says, Social Security disability benefits function as unemployment insurance.

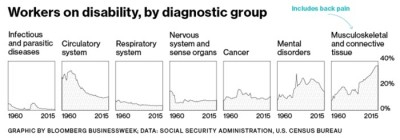

In 1956, when the disability insurance fund was created, qualification was based on a list of accepted medical conditions. In 1984, Congress broadened the criteria, giving more weight to chronic pain and mental disorders. The qualification process also became more subjective. Now, rather than check diagnostic conditions against a list, the process determines whether applicants are able to perform work that’s available. “It’s not as if you go to the doctor, the doctor says, ‘I’m sorry, son, you’ve got disability,’ ” Autor says. “It’s a social construct, because it’s about whether you can work.”

In Van Buren County, Ark., 11.3 percent of working-age adults get federal disability benefits, putting it in the top 5 percent nationally. It’s been a tough decade for the county. In 2006, Volex moved a plant that made electrical cable to Hermosillo, Mexico. Pilgrim’s closed its poultry processing plant in 2008, eliminating 300 jobs. That same year, a tornado destroyed Rivertrail Boat, which had employed 30 people. There’s a Walmart Supercenter on the state highway, but in Clinton, the county seat, about half the shops on Main Street are shuttered.

Resident Christa Cossey found work at age 20 as a long-haul truck driver, a well-paid job for someone without a college degree. Now 51, she’s been on disability since 2008 because of ailments related to her years of driving: obesity, asthma, atypical chest pain, diabetes, fibromyalgia, high blood pressure, and arthritis in her neck, shoulders, elbows, wrists, and fingers. She also suffers from degenerative disc disease, degenerative joint disease, and bulging discs in her lower back.

During her approval process, a vocational expert testified that Cossey could perform sedentary work, such as at a call center, with frequent breaks. No jobs fitting that description are available in Van Buren County, and Cossey and her husband—who gets disability payments for his cerebral palsy—don’t want to move away from family. Instead, she supplements her $1,000 disability check with part-time work as a “secret shopper,” checking up on retail employees. She makes less than $810 a month. “I would work as much as my body would let me,” she says. “I went from making over a thousand dollars a week to making less than that a month. It was hard.”

Shannon Cleveland, a nonprofit employee who’s paid through a grant from the Social Security Administration to help people on disability navigate the complicated rules for going back to work, says the way the program is structured can trap people who live in low-wage areas like Van Buren County. Recipients are often hesitant to look for full-time employment because they don’t want to risk losing the financial cushion and access to health care that disability insurance provides. “It’s scary to try to work,” says Cleveland, herself a quadriplegic after surviving a car accident at 17. “I talk to people who could work, and they’re crying.”

Interest from Congress tends to spike when the disability fund is almost out of money. In 2015 it required Social Security’s Office of the Inspector General (OIG) to open joint fraud investigation offices with local officials in all 50 states. These offices first opened in the late 1990s. In 2013 fraud made up a little more than 70 percent of the OIG’s caseload; it’s now 86 percent. But outright fraud is unlikely to explain all the program’s growth. The OIG reports that its fraud units saved the fund $416 million in 2015; total payments that year were $89 billion.

In the coming Congress, Republican Representative French Hill, who represents Van Buren County, plans to reintroduce a disability insurance reform bill he wrote after hearing Autor, the MIT economist, present his analysis of the program—a talk that echoed things Hill had heard from folks back home. The bill would require more frequent reviews of disability recipients with nonpermanent conditions. It would also allow recipients to keep some of the subsidy even after they’re employed rather than being cut off. “The cliff aspect of it is a frustrating flaw in many federal safety net programs,” Hill says. Asked whether he thinks lagging economic growth helps explain why so many of his constituents have turned to disability insurance, he answers, “Undeniably.” But, he adds, “that’s not a reason not to think critically about the program.”

The bottom line: Economists believe declining job prospects and an aging workforce, not fraud, explain the growth of disability claims.

แสดงความคิดเห็น

รายละเอียดกระทู้

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2016-12-16/mapping-the-growth-of-disability-claims-in-america Where jobs vanish, disability insurance is the safety net. Mapping the Growth of Disability Claims in America If you’ve paid into Social Security, become injured or sick, and can no longer earn more than $1,130 a month, you can get a monthly subsidy from Social Security’s Disability Insurance Trust Fund. In 1990 fewer than 2.5 percent of working-age Americans were “on the check.” By 2015 the number stood at 5.2 percent. That growth has left the fund in periodic need of rescues by Congress—most recently in 2015, when the Bipartisan Budget Act shifted money from Social Security’s old-age survivors’ fund to extend the solvency of the disability fund to 2023. “None of us should be surprised that the cost of the program was rising,” says Stephen Goss, Social Security’s chief actuary. He says the program’s growth is mostly a consequence of demographic change. Older workers are more likely to get sick, and as women have entered the workforce, they too have become eligible for benefits. The geographic distribution of people on disability tells a different, but complementary, story: Workers who might have endured pain for a physical job apply for disability when jobs disappear. This has created what some economists call “disability belts”—rural areas in Appalachia, the Deep South, and along the Arkansas-Missouri border. Mapping the Growth of Disability Claims in America In a 2013 paper, David Autor, an economist at MIT, and his co-authors wrote that Social Security disability insurance was the single biggest source of federal transfers into areas that had been directly affected by trade with China and Mexico. Dan Black, now at the University of Chicago, found in a 2004 paper that growth in disability claims in Appalachia dramatically outpaced those in the rest of the country. Although it’s not designed to, Autor says, Social Security disability benefits function as unemployment insurance. In 1956, when the disability insurance fund was created, qualification was based on a list of accepted medical conditions. In 1984, Congress broadened the criteria, giving more weight to chronic pain and mental disorders. The qualification process also became more subjective. Now, rather than check diagnostic conditions against a list, the process determines whether applicants are able to perform work that’s available. “It’s not as if you go to the doctor, the doctor says, ‘I’m sorry, son, you’ve got disability,’ ” Autor says. “It’s a social construct, because it’s about whether you can work.” In Van Buren County, Ark., 11.3 percent of working-age adults get federal disability benefits, putting it in the top 5 percent nationally. It’s been a tough decade for the county. In 2006, Volex moved a plant that made electrical cable to Hermosillo, Mexico. Pilgrim’s closed its poultry processing plant in 2008, eliminating 300 jobs. That same year, a tornado destroyed Rivertrail Boat, which had employed 30 people. There’s a Walmart Supercenter on the state highway, but in Clinton, the county seat, about half the shops on Main Street are shuttered. Resident Christa Cossey found work at age 20 as a long-haul truck driver, a well-paid job for someone without a college degree. Now 51, she’s been on disability since 2008 because of ailments related to her years of driving: obesity, asthma, atypical chest pain, diabetes, fibromyalgia, high blood pressure, and arthritis in her neck, shoulders, elbows, wrists, and fingers. She also suffers from degenerative disc disease, degenerative joint disease, and bulging discs in her lower back. During her approval process, a vocational expert testified that Cossey could perform sedentary work, such as at a call center, with frequent breaks. No jobs fitting that description are available in Van Buren County, and Cossey and her husband—who gets disability payments for his cerebral palsy—don’t want to move away from family. Instead, she supplements her $1,000 disability check with part-time work as a “secret shopper,” checking up on retail employees. She makes less than $810 a month. “I would work as much as my body would let me,” she says. “I went from making over a thousand dollars a week to making less than that a month. It was hard.” Shannon Cleveland, a nonprofit employee who’s paid through a grant from the Social Security Administration to help people on disability navigate the complicated rules for going back to work, says the way the program is structured can trap people who live in low-wage areas like Van Buren County. Recipients are often hesitant to look for full-time employment because they don’t want to risk losing the financial cushion and access to health care that disability insurance provides. “It’s scary to try to work,” says Cleveland, herself a quadriplegic after surviving a car accident at 17. “I talk to people who could work, and they’re crying.” Interest from Congress tends to spike when the disability fund is almost out of money. In 2015 it required Social Security’s Office of the Inspector General (OIG) to open joint fraud investigation offices with local officials in all 50 states. These offices first opened in the late 1990s. In 2013 fraud made up a little more than 70 percent of the OIG’s caseload; it’s now 86 percent. But outright fraud is unlikely to explain all the program’s growth. The OIG reports that its fraud units saved the fund $416 million in 2015; total payments that year were $89 billion. In the coming Congress, Republican Representative French Hill, who represents Van Buren County, plans to reintroduce a disability insurance reform bill he wrote after hearing Autor, the MIT economist, present his analysis of the program—a talk that echoed things Hill had heard from folks back home. The bill would require more frequent reviews of disability recipients with nonpermanent conditions. It would also allow recipients to keep some of the subsidy even after they’re employed rather than being cut off. “The cliff aspect of it is a frustrating flaw in many federal safety net programs,” Hill says. Asked whether he thinks lagging economic growth helps explain why so many of his constituents have turned to disability insurance, he answers, “Undeniably.” But, he adds, “that’s not a reason not to think critically about the program.” The bottom line: Economists believe declining job prospects and an aging workforce, not fraud, explain the growth of disability claims.

จัดฟอร์แม็ตข้อความและมัลติมีเดีย

รายละเอียดการใส่ ลิงค์ รูปภาพ วิดีโอ เพลง (Soundcloud)